What is “Italian Sounding”, what does it represent and what risks does it entail?

A relatively unknown phenomenon for non-experts, with a vaguely musical and not at all threatening connotation, “Italian Sounding” represents a sort of plague, a wound that needs continuous and ever urgent treatment and whose effects inexorably spread over the economic fabric.

It is simple to explain, as much as it is terribly complicated the struggle to manage it and keep it under control, especially by the authorities responsible for protecting the average consumer; in fact, this latter is culturally very little prepared to understand and judge the goodness and real origin of a product. The phenomenon consists in the imitation, above all (but not only) in the agro-food field, of products, denominations and brands, by exploiting any element that can in some way evoke a vague concept of Italian identity.

All of this, it goes without saying, without practically the slightest objective feedback. So you are facing labels referring to cities, famous places, and typical expressions and, in short, a whole series of misleading indications that turn bad quality products into substitutes of great and noble products that apparently come from Italy. This is a strongly rooted phenomenon abroad, particularly in the states of both North and South America, but also in European markets.

It is true that we are experiencing a very delicate moment, which was caused by an unexpected and dramatic pandemic that, most likely, is destined to transform the general context for an unspecified period of time; nonetheless, except for that, Italy has been one of the most significant destinations for food and wine tourism in the world, with an impressive turnover, and there are no reasons to think it will not be like that once the emergency will be over. The interest in this Italian sector clearly goes on also once the tourist has returned home, because at that point they start looking for “made in Italy” products or supposedly so.

This is why many foreign companies, taking advantage of the universal popularity of some typically Italian products, unscrupulously (and improperly) use names, brands and images, often misrepresenting them to the point of ridicule. In this way, in fact, they obtain the attention of the consumer and persuade him to buy food and objects that are completely unrealistic both from a qualitative and an allegedly Italian origin point of view.

One wonders, then, what is the practicable way to contrast a phenomenon that damages both the image of products and the culture of quality; above all because, contrary to what one might think, what reaches the market in “Italian sounding” mode does not necessarily correspond to what is meant by counterfeiting, which is punished by precise norms when brands are guaranteed copyright protection or recognition of the designation of origin.

Counterfeiting has to do with offenses that violate a registered trademark, a denomination of origin or even a design, and can even lead to the falsification of the product itself, an issue that can also have serious effects on health and hygiene.

Actually, the concept of “Italian sounding” – which does not exist if not in relation to Italian identity – is based on elements that could often evoke a different origin, because the production is local and only the product name keeps some Italian traits. Finally, it is a phenomenon that is not mentioned in any regulation and generally impacts on an Italian product without violating any law of the foreign country where it occurs.

Speaking of numbers, to get an idea of how impressive they are, the latest available data (Coldiretti study source on the occasion of the presentation of the rules on the obligation to indicate on the label the origin of all foods – Law no. 12 of February 11, 2019) refer to more than 100 billion euro in value for fake Made in Italy, with an increase of 70% over the last ten years “as a result of international piracy that improperly uses words, colors, locations, images, denominations and recipes that recall Italy for fake foods having nothing to do with the national production system.“

What greatly expands the phenomenon of fakes is precisely what Coldiretti defined as the “hunger” for Italy abroad, an attitude that generates and multiplies low cost imitations, but also fosters trade wars arising from political tensions.

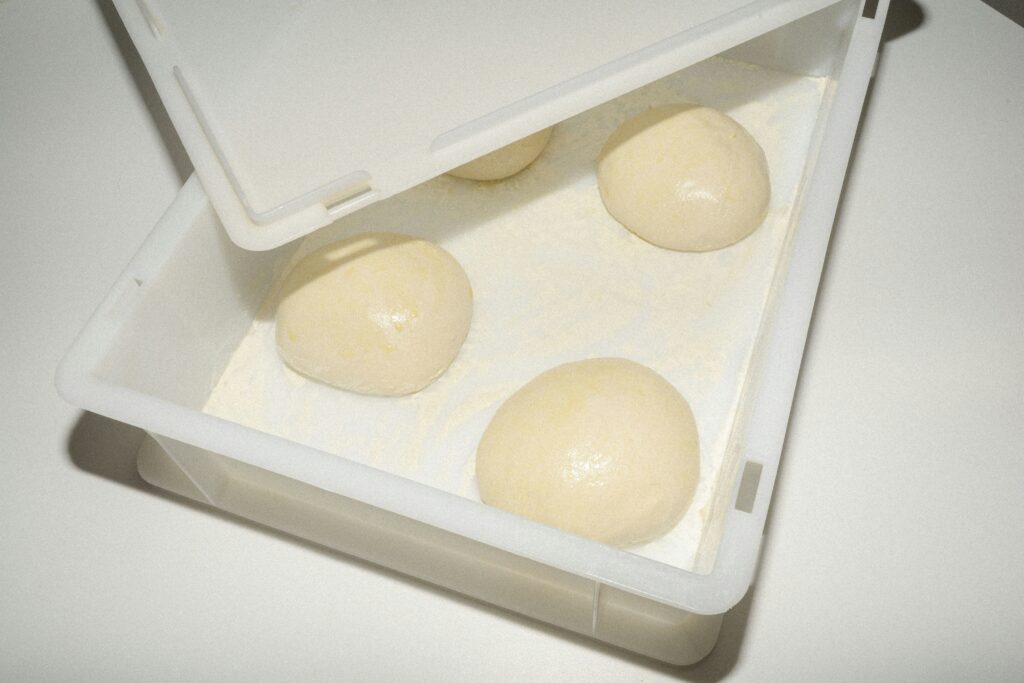

This is the case of the Russian embargo which triggered a proliferation of locally produced fake Made in Italy food: from “Casa Italia” mozzarella to “Buona Italia” salad, from “Milano” mortadella to “Parmesan” and burrata cheese, all “delicacies” made in Cyrillic. Of course, bilateral trade agreements such as Ceta with Canada are also of concern. For the first time, these agreements explicitly allow the rough imitation of prestigious Italian products using names such as Asiago, Fontina, Gorgonzola, Prosciutto di Parma and San Daniele, not to mention Parmesan, which is freely produced and marketed in North America.

So, it turns out that abroad more than two out of three “Italian” products are fake and the growth rate of agri-food exports – amounting to 41.8 billion Euros in 2018 – has been reduced to a quarter compared to 7% of the previous year. Stricter regulations on the labeling of the food origin would certainly be necessary, as this is something that affects, although in a different way, every Italian product, from wine to salami and pasta. Moreover, Coldiretti underlined that, in an apparently anomalous way, imitations of Italian food do not come from poor countries but from emerging and richer ones, such as United States and Australia.

At the top of the list of counterfeit products are cheeses such as Parmigiano Reggiano and Grana Padano, which have more copies in circulation than originals; just to mention a couple of them, besides the universal Parmesan, there are the Brazilian parmesao and the Argentinian reggianito. Besides other famous cheeses, among wines there are Bordolino from Argentina having the Italian flag on the label, German Kressecco and Californian Chianti, not to mention South American Marsala.

Not even e-commerce is saved from this fake food invasion, because on the net you can buy Provolone and Asiago from Wisconsin, Canadian Robiola and Fontina made in China! It is, therefore, an extremely complicated task which will require years of non-stop awareness and activity, the one awaiting people and authorities who are responsible, if not for the improbable elimination of the many poor quality Italian sounding products, at least for providing accurate information on their origin and organoleptic characteristics. Certainly, there are many paths to follow and they clash with more than one obstacle, starting from the little attention that even Italian consumers pay to the origin of a product or to the reading of a label; moreover, it is necessary to highlight the almost non-existent interest in foods that may have a higher cost but can give totally different emotions, aromas and scents.

This is about implementing a serious, targeted and effective communication, which must be first strengthened within our borders and then exported in a convinced way. By doing this, it will be possible to create synergic actions among the involved actors, starting from producers to get to decision makers in the political field, passing through the inestimable food and wine heritage which is fully part of Italian culture and traditions.